Future Data Systems

Insights from the Carnegie Mellon seminar series

Based on the Future Data Systems Seminar Series — Fall 2025, we could get great insights about what matters for current and future data systems. Understand what happens in the market to advance todays approaches.

The Overview

If you don’t have much time to read everything or watching the videos, just take that with you:

Apache Iceberg: Iceberg uses a hierarchical metadata structure to minimize data reads through efficient file pruning.

Apache Hudi: Hudi enables high-frequency streaming updates using non-blocking concurrency control and transactional timelines.

DuckLake: DuckLake improves performance by moving table metadata from object storage files into a transactional database.

Vortex: Vortex is a modular file format designed for extreme throughput using hardware-optimized lightweight encodings.

Apache Arrow ADBC: ADBC provides a universal columnar connectivity API to eliminate CPU overhead during high-speed data transfer.

SingleStore: The Bottle Service enables instant database branching by tracking references to immutable data blocks in object storage.

Delta Lake: Delta Lake supports atomic multi-statement and multi-table transactions to enable complex data warehouse migrations.

Mooncake: Mooncake implements composable HTAP by mirroring transactional data into a real-time analytical layer with sub-second latency.

Firebolt: Firebolt achieves sub-second query speeds on Iceberg by caching snapshots and reusing intermediate query artifacts.

XTDB: XTDB is a bitemporal database that reconstructs historical states by replaying immutable event logs in reverse.

Apache Polaris: Polaris acts as an open REST-based catalog providing centralized governance and dynamic credential vending.

Apache Fluss: Fluss provides low-latency streaming storage specifically designed for real-time analytical workloads and materialized views.

But if you have the time, dive into the aspects that maybe coin our future data systems.

An Extremely Technical Overview of How Apache Iceberg Planning Actually Works

by Russell Spitzer (YouTube)

The fundamental goal of query optimization is to read less data. This efficiency is achieved by utilizing metrics associated with data files to determine their relevance to a given query. The core mechanism for this is the use of File Metrics/Min-Max Ranges, which are metadata fields included in columnar file formats like Apache Parquet that specify the minimum and maximum values for columns within that file. These ranges allow the query planner to decide whether a file must be read purely based on the query constraints. The move to cloud storage (like S3) made table formats necessary, as operations like checking file footers became extremely expensive due to charging per API call. Apache Iceberg, an open table format, was introduced to address this by treating a collection of files like a relational database, offering features such as ACID transactions and partitioning optimized for cloud scale.

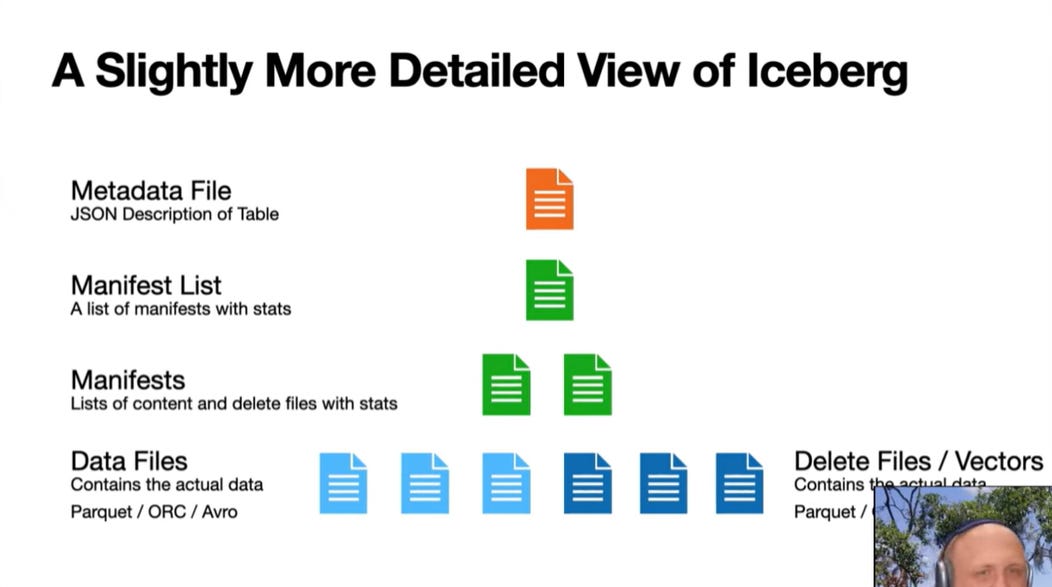

Fig. 1: How Apache Iceberg is build

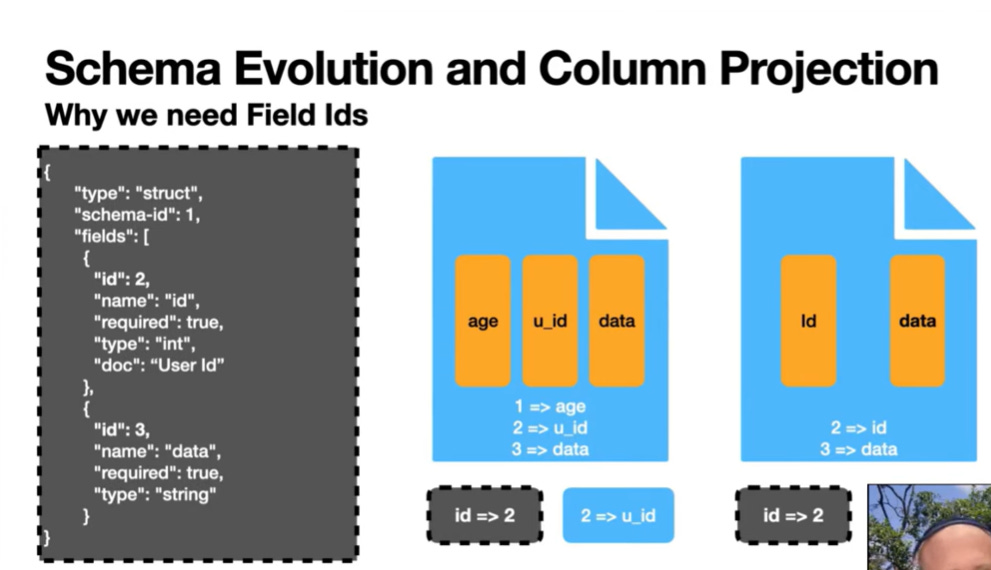

Iceberg organizes its metadata in a hierarchical structure: the main metadata.json file points to Snapshots, which list Manifest Lists, which list Manifest Files, which finally reference the actual data and delete files. When planning a query, the system converts engine-specific predicates into the Iceberg expression language and performs binding based on Field IDs. These are unique identifiers assigned to every column in the schema. Field IDs decouple the column’s logical name from its physical storage, which is key for successful schema evolution because renaming a column does not require rewriting the underlying data files.

Fig. 2: Schema Evolution and Field ID’s

Iceberg further optimizes filtering through hidden partitioning, meaning predicates defined on data columns (like a timestamp) can be converted into expressions that work directly against partition metrics, allowing for efficient pruning without the user knowing the partition scheme.

Apache Hudi: A Database Layer Over Cloud Storage for Fast Mutations & Queries

by Vinoth Chandar (YouTube)

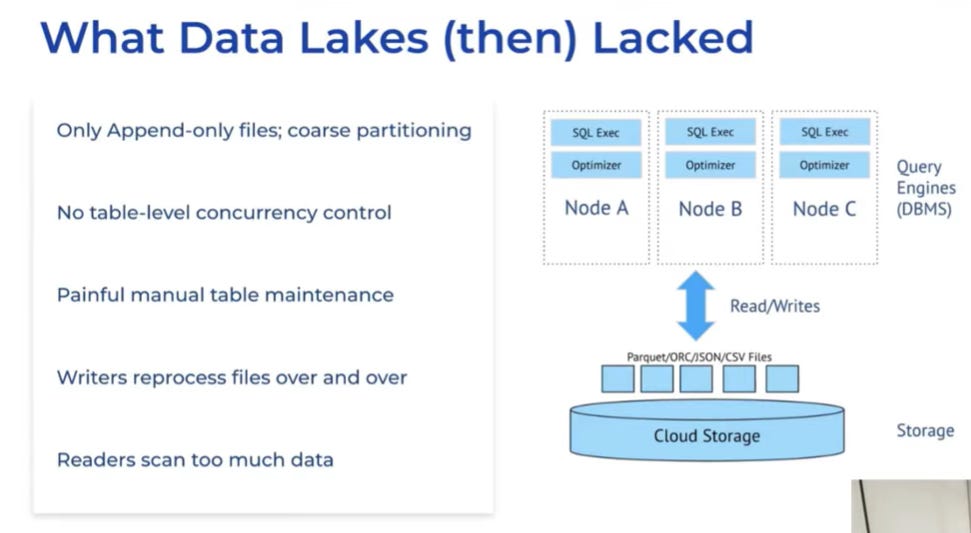

Apache Hudi was developed to counteract the limitations of traditional, file-based data lakes, which often suffered from correctness issues and excessive reprocessing requirements.

Fig. 3: Limitations of traditional file-based Data Lakes

Hudi provides database discipline—such as updates, deletes, and transactional indexes—by embedding a storage engine functionality into distributed SQL engines.

Fig. 4: How Apache Hudi works

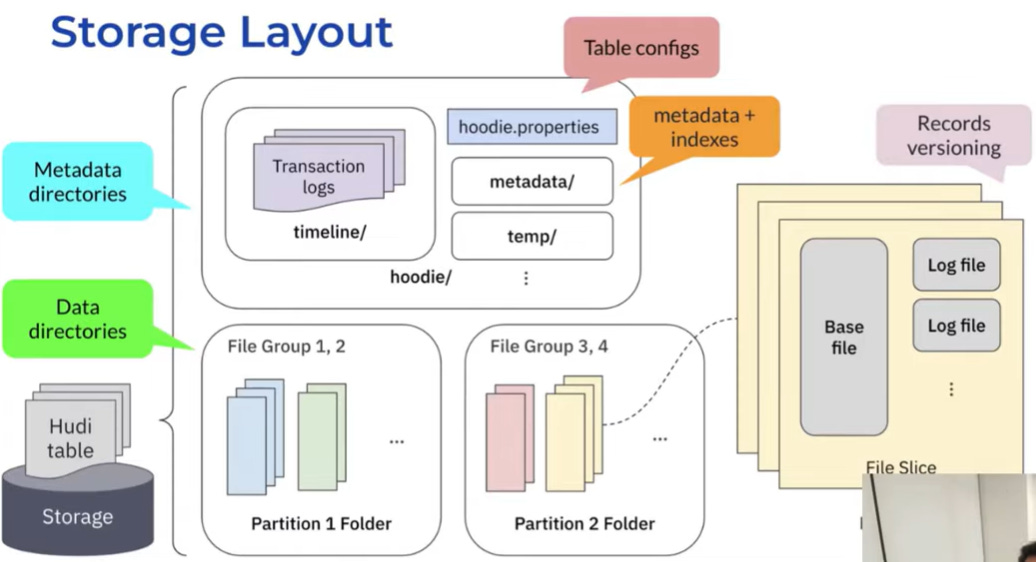

Hudi organizes data into File Groups within a partition, with each group containing different versions of records organized in File Slices. A File Slice consists of a columnar base file (Parquet or ORC) and optional log files that encode recent updates or deletes.

Fig. 5.: How Apache Hudi organizes data

This structure supports two primary table types: Copy-on-Write (COW), which leads to higher write costs but faster query performance, and Merge-on-Read (MOR), which uses the log files for faster writes and periodically merges these changes into new base files via compaction. Central to Hudi’s operation is the Timeline, a transactional event log that records every action (any change to the table state, including writes and maintenance). To ensure consistency, Hudi uses Optimistic Concurrency Control (OCC) at a file-group level. A significant feature supporting high-throughput streaming workloads is Non-Blocking Concurrency: compaction plans are serialized to the Timeline, allowing readers and writers to immediately adjust their view of the table state while the resource-intensive compaction process runs in the background, preventing writer starvation. Furthermore, Hudi optimizes for record-level updates through columnar writes, where only the changed columns are written to the log files, thereby reducing the total bytes written and lowering update latency.

DuckLake: Learning from Cloud Data Warehouses to Build a Robust “Lakehouse”

by Jordan Tigani (YouTube)

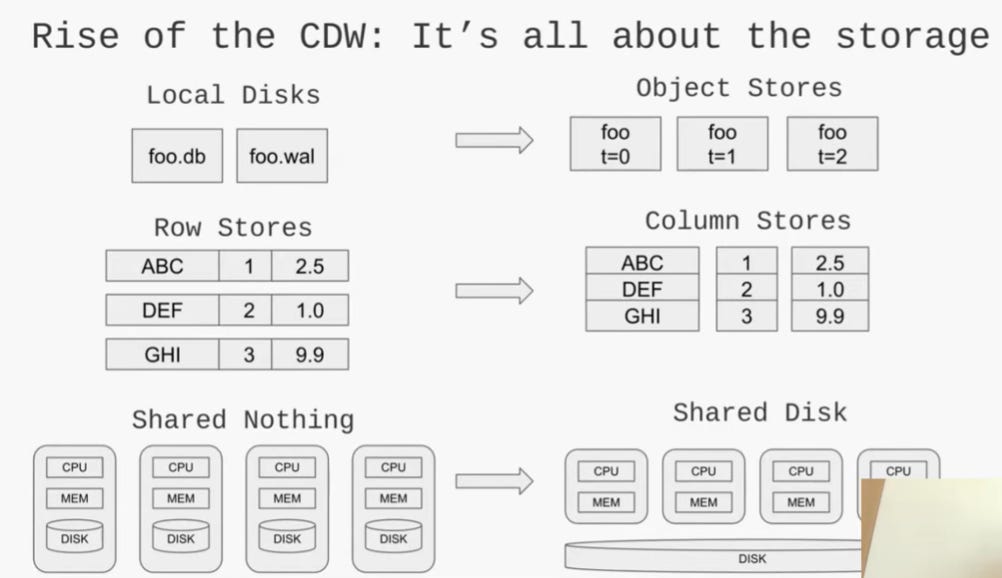

The philosophy behind DuckLake stems from the convergence of lakehouse architectures with traditional Cloud Data Warehouses, concluding that databases are a better place to store metadata than object stores.

Fig. 6: Rise of the Cloud Data Warehouse

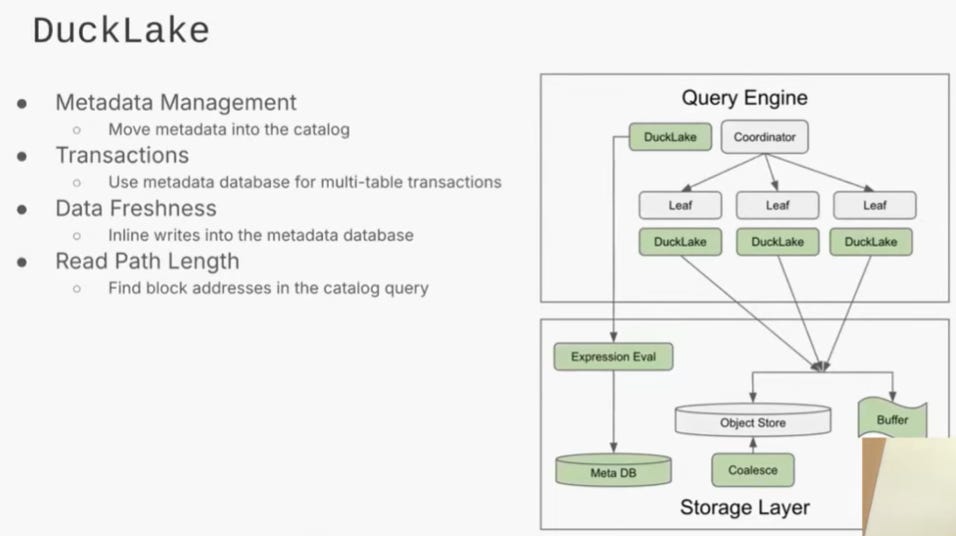

DuckLake is an open data format that shifts the management of metadata (including file references and column statistics) from object storage into an external, transactional database. By relying on a database, DuckLake can ensure all metadata modifications occur within a single database transaction, thus providing robust ACID properties (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability) for table commits.

Fig. 7: Handling of metadata in DuckLake

This architecture enables efficient File Pruning—the filtering out of irrelevant data files—by executing standard SQL queries directly against the metadata tables (like ducklake_file and ducklake_column_stats). For handling modern, high-frequency ingestion, DuckLake addresses the “fresh data” problem by buffering small, frequent updates in a catalog table (an in-memory row store) that is instantly queriable, delaying the need for expensive file rewriting and compaction.

Vortex: LLVM for File Formats

by Will Manning (YouTube)

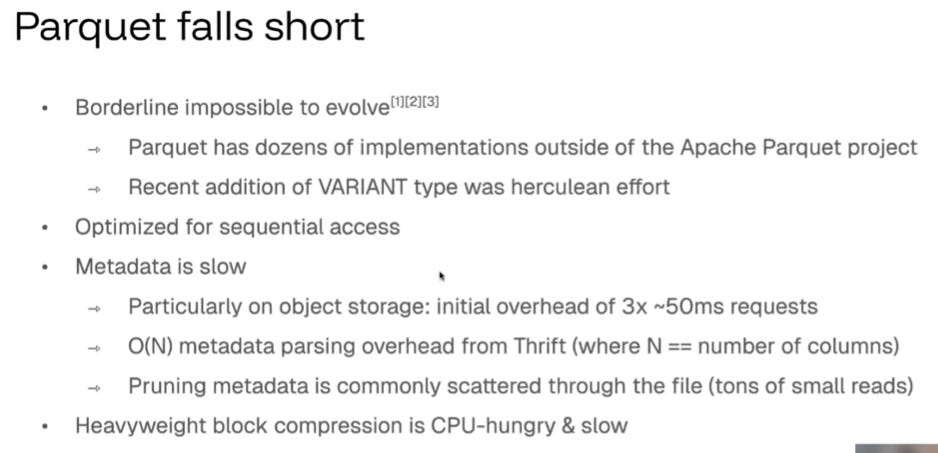

Vortex is an open-source, extensible columnar file format designed to solve the limitations of existing formats like Parquet, which suffer from difficult evolution, slow compression, and poor metadata access for wide tables.

Fig. 8: Where Parquet falls short

Vortex positions itself as a modular framework (the “LLVM for file formats”). Extensibility is achieved by shifting design decisions from the spec to the file writer, utilizing core modular components: Logical Types (handling complex schema information), Arrays (encapsulating cascaded compression and deferring computation), and Layouts (defining the physical byte structure, allowing the deferral of I/O). Vortex prioritizes lightweight compression techniques (like Fast Lanes Bit Packing, ALP, FSST) over high-ratio codecs (like Zstandard), achieving extremely high decompression throughput (e.g., 53 GB/s for Bit Packing). Efficient metadata lookup is ensured by storing the file’s top-level topology in a small, fixed-size Postscript (metadata footer, max 64KB), which contains offsets and lengths, minimizing high-latency I/O. Finally, Vortex implements an extremely optimized Scan Operator which supports Compute Push Down. Query engines submit expressions to this operator, allowing it to perform filters and projections with zero compute for projection expressions.

Fig. 9: Vortex File Format

Where We’re Going, We Don’t Need Rows: Columnar Data Connectivity with Apache Arrow ADBC

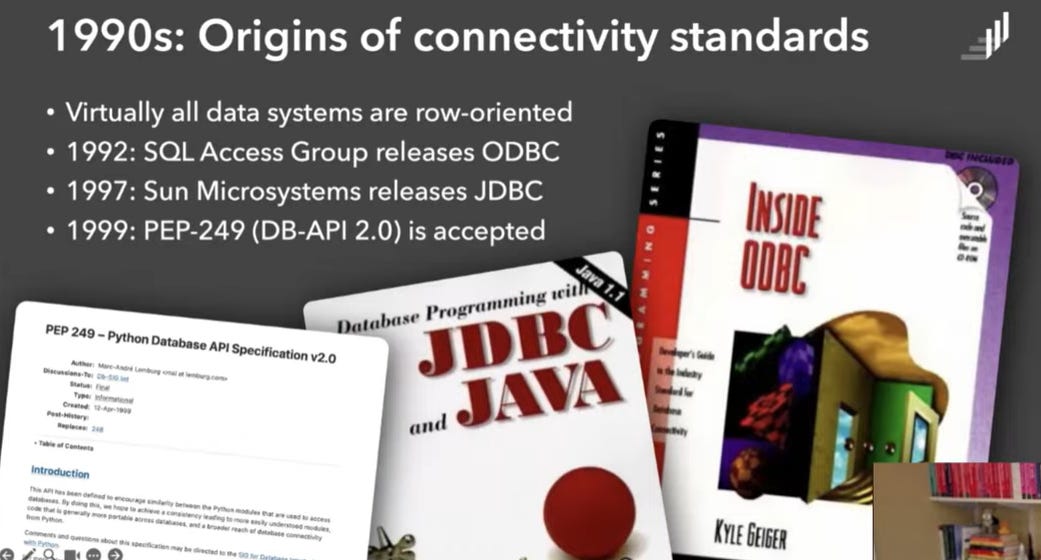

Legacy data connectivity standards like ODBC and JDBC, developed in the 1990s when data systems were row-oriented, are inefficient for modern analytic workloads.

Fig. 10: Orgins of connectivity standards

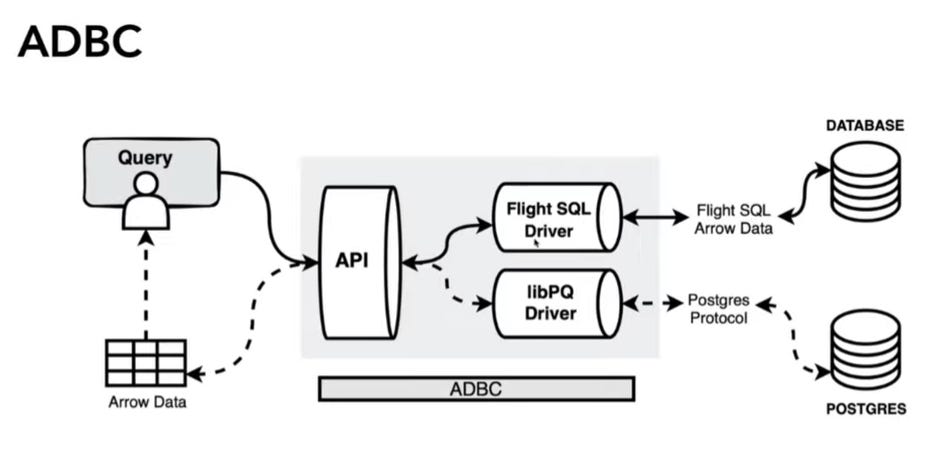

Transferring data between columnar source and columnar destination systems using these standards requires an expensive, CPU-intensive transpose (shuffle) operation at both ends. This inefficiency has turned the bottleneck in modern data transfer from the network (which has improved by 10,000x since the 90s) to the CPU serialization/deserialization cost. ADBC (Arrow Database Connectivity) is a modern, multi-language data access API and driver standard designed specifically for analytic applications. ADBC leverages the Apache Arrow columnar format to transfer query results, enabling zero-copy data transfer between compatible systems, which significantly minimizes CPU load and memory overhead.

Fig. 11: ADBC - Arrow Database Connectivity

ADBC is a client API specification and is not a wire protocol, meaning it imposes no requirements on the server side. This allows ADBC to work via a flexible architecture: a Fast Path for systems that natively support Arrow/Flight SQL, and a Slow Path where the ADBC driver wraps an existing row-based protocol (like libpq for Postgres) and performs the conversion internally. The system relies on a Driver Manager to dynamically load and manage shared library drivers at runtime.

SingleStore: Storage Metadata for Modern Cloud Databases

by Joyo Victor (YouTube)

SingleStore’s Bottomless Storage model, which separates compute from storage in cloud object storage, introduced a significant challenge: without a central reference tracking mechanism, garbage collection (GC) became impossible when features like database branching were introduced.

Fig. 12: Bottomless File Storage

The solution was the Bottle Service (Bottomless Metadata Service), a centralized, external SingleStore database cluster. This service tracks all database metadata and, crucially, records which compute sessions reference which opaque data files (blobs). The Bottle Service enables database branching by defining a new branch as a new compute session. To create the branch, the Bottle Service executes an INSERT SELECT query to copy all blob references from the old session (as of a specific Log Sequence Number - LSN) to the new session, thereby allowing the branches to share physical files immutably while maintaining independent log streams.

Fig. 13: Git-style branches on the database

Furthermore, this symmetric, bidirectional replication structure allows for Smart DR (Disaster Recovery), where a failover to a secondary region (which has been consistently mirrored) is accomplished simply by creating a new branch/compute session in that region.

Multi-statement Transactions in the Databricks Lakehouse

by Ryan Johnson (YouTube)

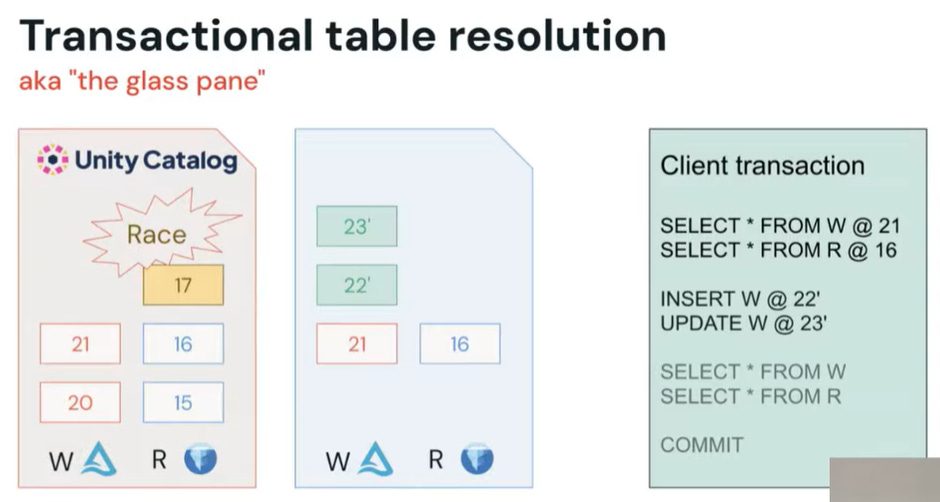

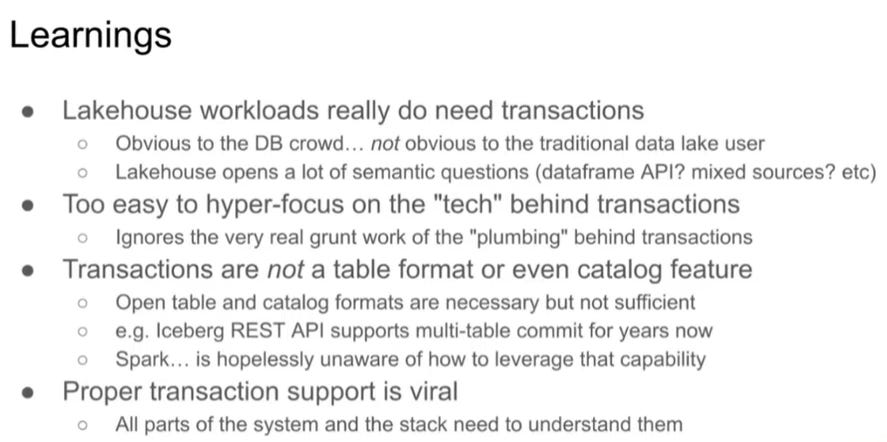

Delta Lake was originally developed to impose discipline on the “data swamp” by using an ordered, atomic sequence of commit files stored in cloud storage. Concurrency control relied on Optimistic Concurrency Control (OCC), where conflicting writers would detect the conflict and retry with a new commit number. However, the most requested feature from migrating data warehouse customers is support for multi-statement, multi-table transactions, which eliminates the need for complex, non-atomic workarounds. This required a major shift: moving away from simple file system-based commits toward catalog-managed rights. Under this new model, writers propose commits to a central Catalog, which is then responsible for validation (e.g., schema enforcement) and ratification, thus enforcing governance and coordination across multiple objects. Isolation is achieved through a conceptual Glass Pane.

Fig. 14: The Glass Pane for transactions

The engine running the transaction tracks the transaction’s own unpublished commits, allowing the transaction to read its own changes while insulating it from external concurrent commits until the transaction commits atomically. Implementing transactions is a highly invasive and viral engineering effort, requiring changes not only to the transaction protocol but also the SQL parser (to distinguish between SQL blocks and true transactions), the serverless gateway, and client UIs. The system also imposes a Transaction Semantics Restriction, preventing transactions from accessing non-transactional sources (e.g., a raw file directory) unless explicitly annotated, to avoid invalidating the transaction’s state.

Fig. 15: Learnings for the Data Lakehouse

Mooncake: Real-Time Apache Iceberg Without Compromise

by Cheng Chen (YouTube)

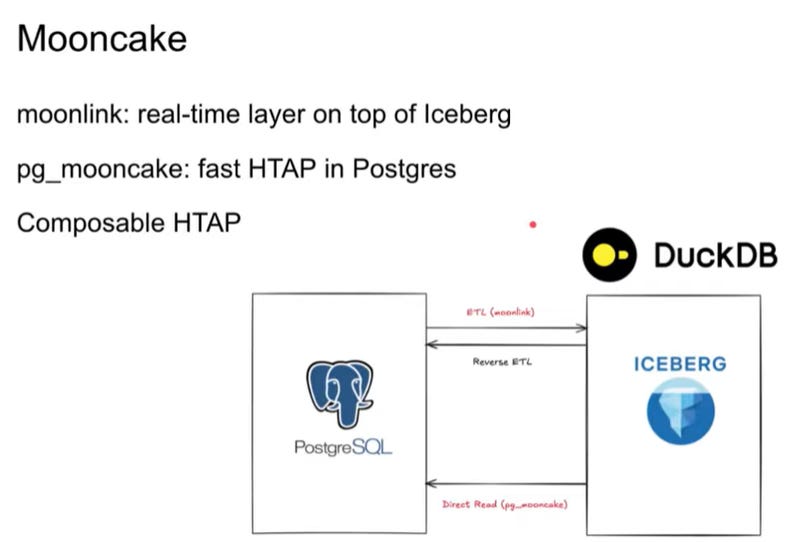

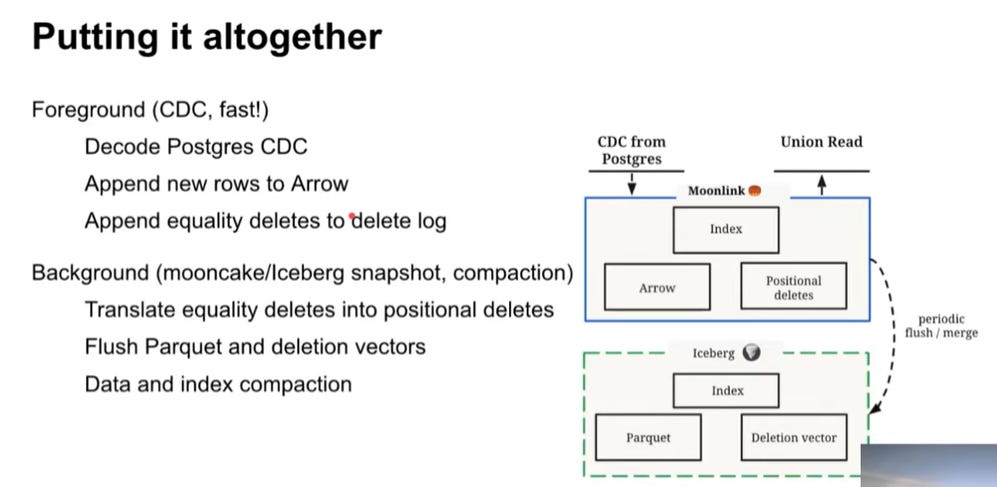

The goal of Mooncake is Composable HTAP, which seeks to bridge existing OLTP systems (like Postgres) with OLAP Lakehouse formats (like Iceberg) to enable fast analytics on fresh transactional data.

Fig. 16: Moonlink - A real-time Layer on top of Iceberg

This is achieved through Moonlink, the real-time layer designed for sub-second ingestion latency. Moonlink decouples its own Mooncake Snapshots (taken frequently, e.g., every 500ms) from the less frequent Iceberg snapshots. It handles streaming inserts efficiently by buffering recent changes in an in-memory Arrow buffer and serving results via a union read that combines the buffer with older Iceberg files. A key technical challenge is translating Postgres’s equality deletes (based on primary key identity) into positional deletes (based on physical file location), which Iceberg requires for efficient reads. Moonlink solves this using a hash index that maps the replica identity to the row’s physical position. To ensure a predictable user experience, Mooncake aims for session-level consistency: when a user makes a write in the transactional system, the subsequent analytical read submits the last commit LSN (Log Sequence Number) to Moonlink, which guarantees that the returned snapshot includes the corresponding mirrored change.

Fig. 17: Overall approach for Mooncake

Firebolt: Why Powering User Facing Applications on Iceberg is Hard

by Benjamin Wagner (YouTube)

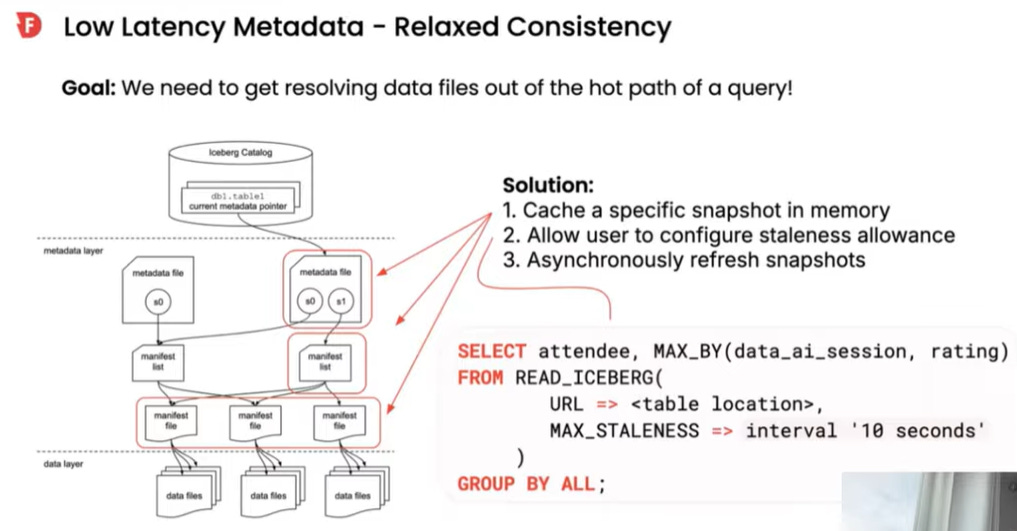

Firebolt focuses on enabling low latency (sub-200ms) queries for user-facing applications. A key challenge is that the sequential resolution of Iceberg’s hierarchical metadata structure requires multiple high-latency reads from object storage, resulting in a theoretical minimum query latency of approximately 0.5 seconds. To achieve speeds below this threshold, Firebolt bypasses the metadata resolution path during the query hot path by caching the entire Iceberg snapshot (the list of data files) in main memory. This strategy relies on the user defining a Staleness Allowance, which permits the system to serve results from the cached metadata while the snapshot is refreshed asynchronously in the background.

Fig. 18: How Firebolt enable low latency

Firebolt leverages its own query engine to solve internal planning problems: it determines join cardinality estimates by running an internal SQL query (e.g., SELECT SUM(record_count)) against an exposed metadata table. For distributed queries, Firebolt optimizes joins by recognizing when tables share the same Iceberg partitioning scheme (e.g., bucket partitioning) and implementing a Storage Partition Join. This technique assigns matching data partitions to the same compute node, eliminating the need for a costly network shuffle. Furthermore, Firebolt’s custom Parquet reader uses C++ co-routines and a buffer manager that reads data in fixed-sized 2MB blocks to maximize concurrent I/O and saturate network bandwidth, ensuring data flows downstream as fast as possible.

Reconstructing History with XTDB

by Jeremy Taylor (YouTube)

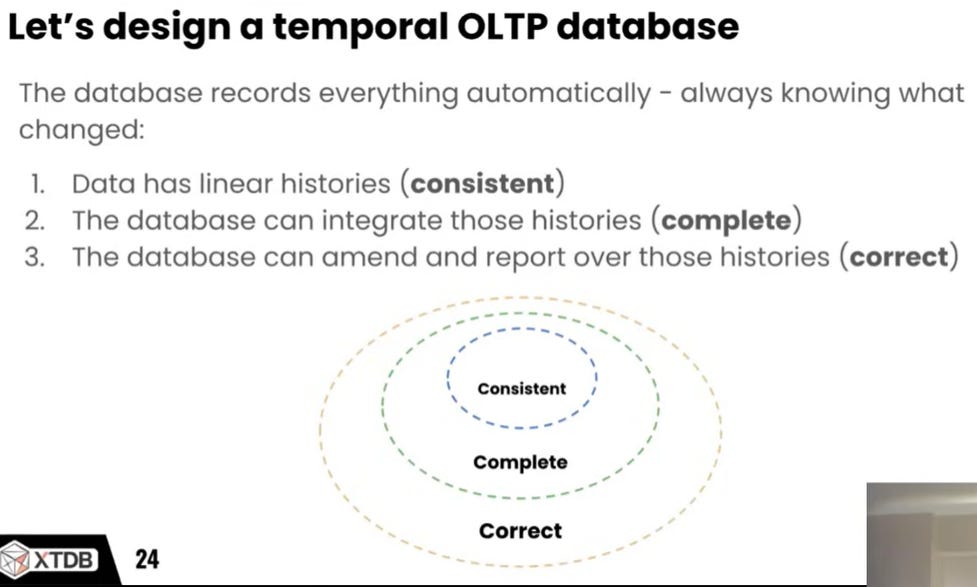

XTDB is a bitemporal database specifically designed for auditability and history reconstruction, leveraging the Bitemporal Model. This model manages change using two independent time dimensions: System Time, the time the data was recorded in the database, and Valid Time, the time the data was true in the real world (user-supplied).

Fig: 19: Design aspects of a temporal OLTP database

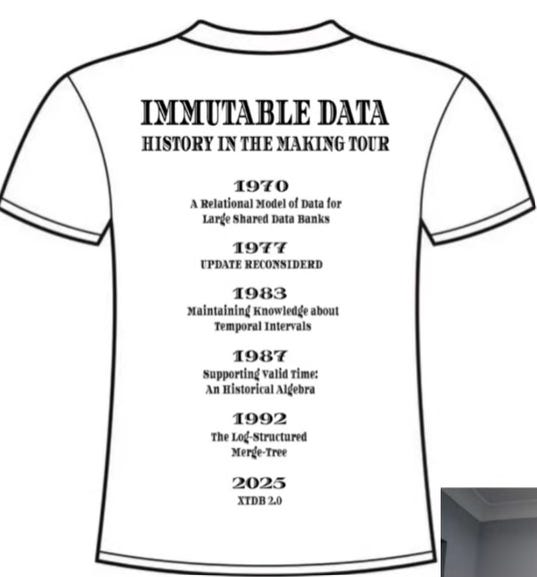

XTDB’s architecture is rooted in an append-only event model. It outsources durability and serialization by using a single-partition Kafka topic as the deterministic Transaction Log. Database nodes consume and deterministically index this log, compacting the data into immutable LSM trees optimized for object storage. The database inherently retains all historical versions. When an update occurs, it is logically treated as an append: the existing version’s time period is closed, and a new version is inserted, maintaining immutability. Crucially, XTDB avoids materializing the full bitemporal state unnecessarily; it is inherently lazy. At query time, it reconstructs the required versions by playing the immutable events in reverse system time order. This process is made efficient by the use of Recency, a heuristic that calculates the maximum timestamp where Valid Time equals System Time for a record. This allows the system to quickly rule out searching through older, irrelevant historical files for “as of now” queries.

Fig. 20: History of immutable data

From Storage Formats to Open Governance: The Evolution to Apache Polaris

by Prashant Singh (YouTube)

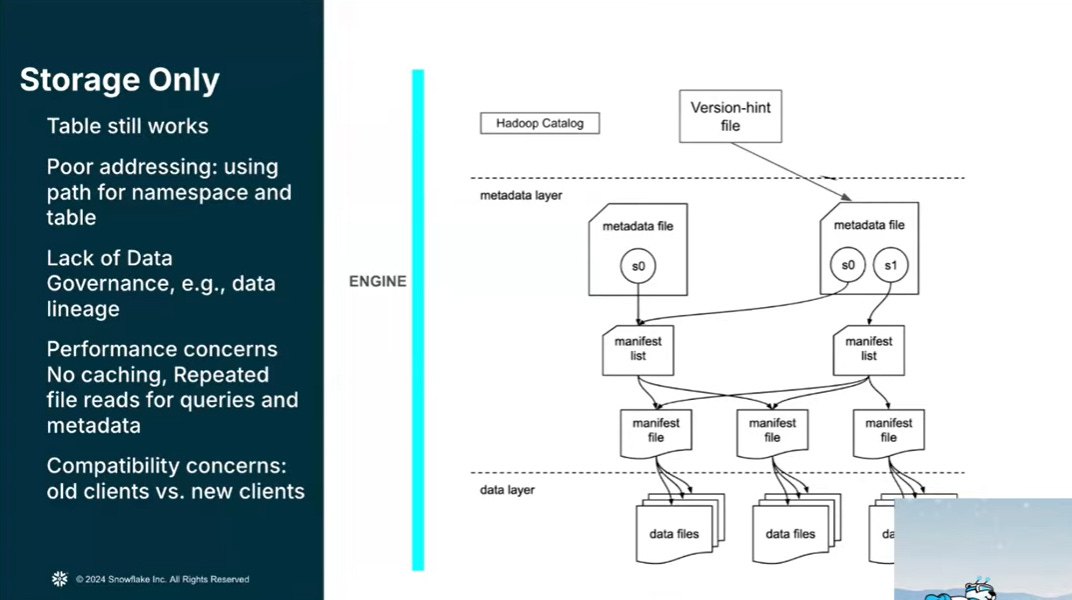

Apache Polaris shifting data lake management from passive, client-side storage tracking to an active, server-side intelligence and governance layer.

Fig. 21: Why Table Formats are not enough

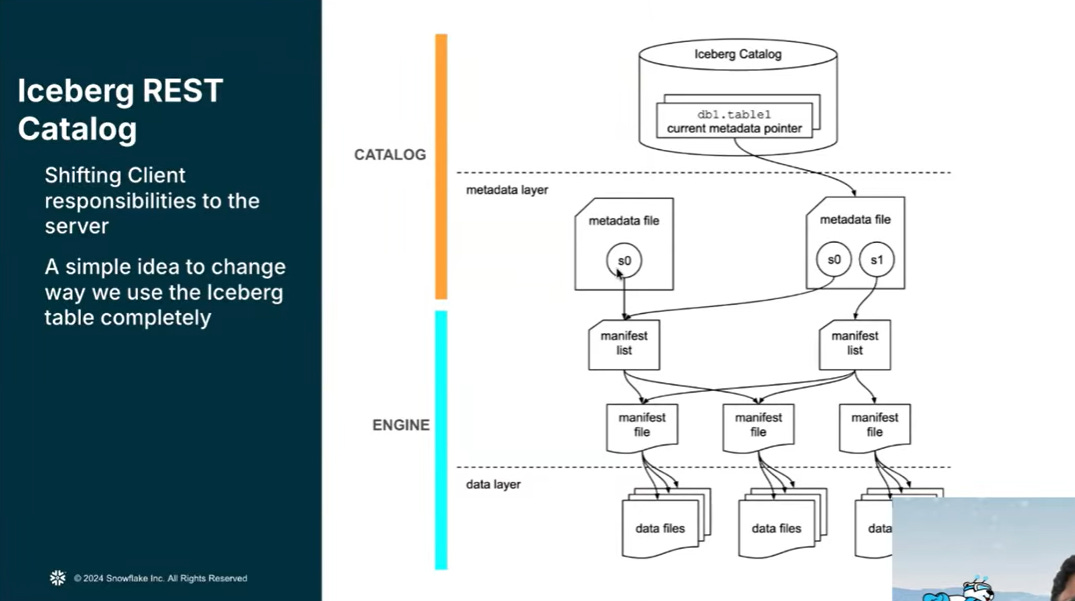

By centralizing the Iceberg REST Catalog specification, it moves the responsibility for metadata generation and table state ownership to the server, which eliminates the need for complex, error-prone client-side lock managers and mitigates the risk of table corruption. This architectural shift enables advanced features previously reserved for traditional databases, such as intelligent conflict resolution—where the catalog can roll back background maintenance to prioritize high-value ingestion—and atomic multi-table transactions.

Fig. 22: Iceberg REST Catalog as metadata layer

Apache Polaris has a focus on open governance and security through Credential Vending, which provides scoped-down cloud tokens to prevent unauthorized storage access, and the enforcement of fine-grained access control (row and column-level security) via “Trusted Engine” relationships. Furthermore, Polaris addresses the fragmented data landscape by acting as a “catalog of catalogs,” capable of federating disparate metadata stores and governing multiple formats like Delta and Hudi. Ultimately, by driving innovations like server-side planning and the V4 metadata specification—which seeks to eliminate redundant file structures in favor of relational-style efficiency—Polaris bridges the gap between the flexibility of data lakes and the robust performance of modern cloud data warehouses.

Apache Fluss: A Streaming Storage for Real-Time Lakehouse

Apache Fluss is bridging the critical gap between real-time stream processing and large-scale analytical storage. Unlike traditional systems that treat streaming (Kafka) and analytical storage (Iceberg) as isolated silos, Fluss introduces columnar streaming storage specifically designed for incremental materialized views at scale.

Fig. 23: Apache Fluss - A streaming table storage for Apache Flink

By utilizing the Apache Arrow IPC format as its native storage and interchange protocol, it enables high-throughput, zero-copy writes and millisecond-latency reads with advanced projection and predicate pushdown executed directly at the file system level.

What makes Fluss truly forward-looking is its Composable HTAP vision: through “Lakehouse Tiering,” it serves as a high-speed, real-time data layer on top of traditional lakehouses. It enables “Union Reads” that transparently stitch together fresh, millisecond-old data with years of historical records into a single, unified table view. This architecture eliminates the need for manual reconciliation between disparate storage layers, transforming the static data lake into a Real-Time Lakehouse capable of delivering both historical depth and immediate, sub-second insights.

Fig. 24: Apache Fluss architecture overview

By integrating primary key support for mutable tables and automated change log generation, Fluss provides the database-like discipline required for modern streaming analytics without compromising on the scalability of the cloud

What a ride! What do you think now about future data system. Just many possible flavors or indeed directions to consider. What will be next steps?

Fantastic breakdown of the Carnegie Mellon seminar series. The shift from client-side to server-side governance with Polaris is probaly the most underrated trend here because it solves the fragmentation problem that's been killling lakehouse adoption. I've watched teams struggle with Iceberg's hierarchical metadata reads for user-facing apps, and Firebolt's snapshot caching approach is exactly the kind of pragmatic workaround that makes things actually useable in production.